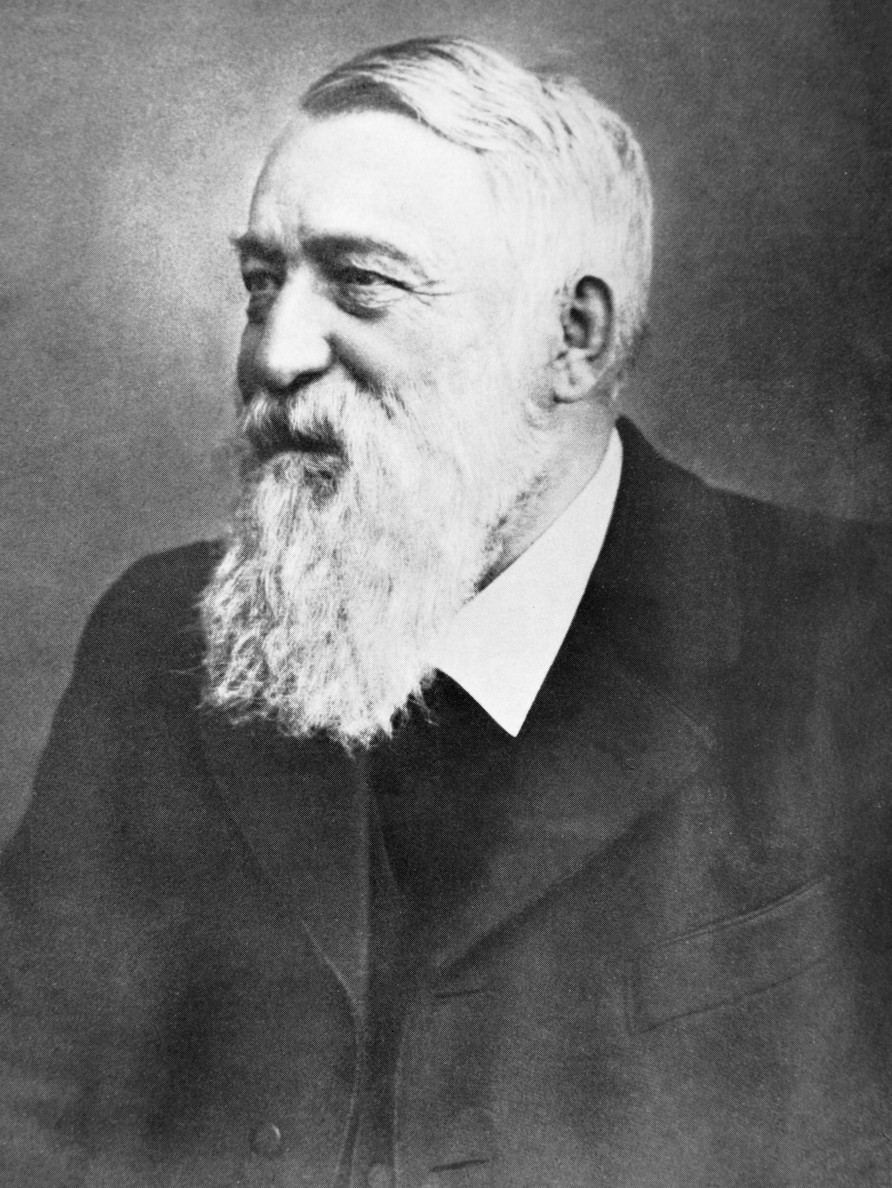

In 1868, all is ready. The first alcohol runs from the distillation apparatus through the condenser. Louis Brüggemann had fulfilled himself a great dream: The north Hessian miller’s son was now a Swabian alcohol manufacturer. A long journey and a golden opportunity. In the middle of the 19th century, Heilbronn offered everything that a courageous entrepreneur’s heart could desire. A look back shows that daring and faith in progress are closely linked to Heilbronn’s story.

Well into the 18th century, Heilbronn was above all an important trading city. Numerous wholesale and long-distance businesses were located there because the location of city on the Neckar offered considerable advantages. The Neckar privilege ensured that the people of Heilbronn could build dams on “their” Neckar at their own discretion so there was no way around the city for merchant ships. As an imperial city, Heilbronn also had important privileges: The stacking right ensured that export traders who wanted to transport their goods past Heilbronn could not move on without unloading their merchandise. Heilbronn based international trading companies knew how to make clever use of this and were increasingly investing in mills in order not only sell raw materials, but also to enhance their value with the help of water-powered equipment. The trading center of Heilbronn flourished.

The mills on the Neckar island of Hefenweiler were forerunners of industrialization. In 1800, however, in most parts of Württemberg there was stagnation and economic decline. The threshold to the 19th century also caused Heilbronn to stumble: The end of the Old Reich brought the loss of imperial freedom along with cherished privileges, Napoleon’s continental blockade limited the long-distance trade and the Congress of Vienna finally began the construction of the Wilhelm Canal. Now ships just sailed past Heilbronn. People had money, but no future prospects. So the Heilbronn trading companies began to reinvent themselves.

They proved their courage, experimented, started early industrial productions and thus increased the level of industrialization in Heilbronn. At the end of the 1840s, Heilbronn boasted the most modern means of transport at the time, the steam engine and steamboat. In the middle of the 19th century, the young industrial site flourished more and more. The good infrastructure and the innovation-friendly atmosphere allowed a wide range of industries to grow. In particular, the food, chemical, paper production, textile and metalworking industries became increasingly diversified. In many branches of industry, Heilbronn companies led in the markets. “Swabian Liverpool” – the comparison is apt: Since 1830, Heilbronn was already one of the cities with the most factories in Württemberg. There was general prosperity. Their good reputation precedes the city. Heilbronn attracts many industrialists and founders from outside as well. Among them Louis Büggemann, who in 1860 stretched his feelers into the Swabian region and sensed his future there.

In 1868 Louis Brüggemann lays the foundations for the enterprise of today.

He came from the North Hessian town of Trendelburg, bringing with him both an education from the local Latin school and experience in agriculture. At Kasseler Hof, the young miller’s son worked as a farmer where he first discovered distilling – and developed an enthusiasm for it. Louis Brüggemann believed in the future of alcohol production from molasses, a byproduct of sugar production. He continued to develop the previous production process – and was successful. In 1865 he took part in founding the brewery Cluss, Brüggemann & Co, which would have a longer history of success in Heilbronn under the brand name Cluss. For Louis Brüggemann himself, it was only a stopover. He had other plans and Heilbronn offered him everything he needed. Louis Brüggemann acquired a building site in 1867 near Bad Straße, located directly on the Neckar. The city administration made the road passable, gave it the name Holz Straße and the future Brüggemann alcohol factory

received the address of number 5. The blueprint for his factory also included a residential building next to the production buildings. After setting up the steam boiler, the grist mill and other equipment, Brüggemann finally received permission to manufacture alcohol in his new factory building on the Neckar.

Louis Brüggemann had reached his goal but his company had only just begun. At the beginning, he employed ten to twelve workers. About half of them were housed in apartments within the factory. Business was going well: Louis Brüggemann expanded in the same year with a one-story depot and the installation of a second steam boiler. His employees received free coal, petroleum and a piece of farmland from the entrepreneur. It is said that they were not left in want of an occasional glass of spirits.